In Fall 2014, I was lucky enough to be invited to play Mozart’s Bassoon Concerto, K. 191 with Sac State’s University Orchestra under the direction of Leo Eylar. The Mozart concerto is the piece that follows bassoonists around for their entire careers. A teacher once told me:

There are two types of auditions: ones that ask for the Mozart concerto, and ones that ask for a concerto of your choice, which means play the Mozart concerto.

I’ve worked on the Mozart concerto on and off since high school, have played it for countless auditions, and have performed it with piano accompaniment. But this was my first shot at playing it with an orchestra, and I decided to mark the occasion by writing my own cadenzas.

Mozart wrote out cadenzas for some of his piano concerti, but none for any of his wind concerti. Performers in his day would have been expected to write—or better yet, improvise—cadenzas of their own. Today, some editions of Mozart’s Bassoon Concerto come with written-out cadenzas, and many other cadenzas are published separately. Prior to last year, I had always used cadenzas written by Milan Turkovic, which are included with the Universal edition of the concerto.

My first step in creating cadenzas of my own was to examine a selection of those written by others, including Bernard Garfield, Jacques Ibert, Frank Morelli, Gabriel Pierné, and Eric Varner (all published by Trevco Music Publishing); Gernot Wolfgang (Doblinger); Milan Turkovic (Jones—not the same as the cadenzas in the Universal edition); and unpublished cadenzas by the late California bassoonist Robert Danziger. I also consulted Sarah Anne Wildey’s 2012 dissertation, which presents and analyzes cadenzas from eighteen bassoonists, including Steven Braunstein, Daryl Durran, Miles Maner, Scott Pool, William Winstead, and Wildey herself.1Sarah Anne Wildey, "Historical Performance Practice in Cadenzas for Mozart’s Concerto for Bassoon, K. 191 (186e)" (DMA Diss., University of Iowa, 2012). Playing through and picking apart all of these helped me develop a sense of what I like (and don’t like) in a cadenza for this piece. I also listened to the twenty-five recordings that I own of the concerto (Harry Searing has catalogued more than 100 extant recordings), learning some licks along the way.

Once I’d digested all of these printed and recorded cadenzas, I set about developing some ideas of my own. I began by just improvising in B‑flat major in a pseudo-Mozartean style during breaks from practicing the concerto proper. When I came up with a chunk of music I liked, I’d write it down. After a few weeks of practice sessions, I had about three pages’ worth of melodic chunks, but they weren’t in any particular order. It took me quite a bit longer to figure out which of these would fit together in what order, to tweak them a bit, and to come up with some extra bits of musical material to glue them together. I didn’t actually write out the cadenzas in their complete form until a couple of days before the performance! But all of time I’d spent working on them made it easy for me to play them from memory in the concert.

In writing my cadenzas, I had three goals:

- reference melodic material from the concerto itself

- quote musical material from elsewhere

- show off some of my strengths

In the first movement cadenza, I took care of goal #1 right away: it begins with a modified version of the concerto’s opening motive, moves to the dominant, goes through another version of the opening motive, and then returns to the tonic. (Only later did I realize that the first few measures of this are similar to the first few measures of the other published set of Milan Turkovic’s cadenzas). The very next passage fulfills goal #2; it’s a quotation from the aria “Non più andrai,” from Mozart’s opera Le Nozzi di Figaro:

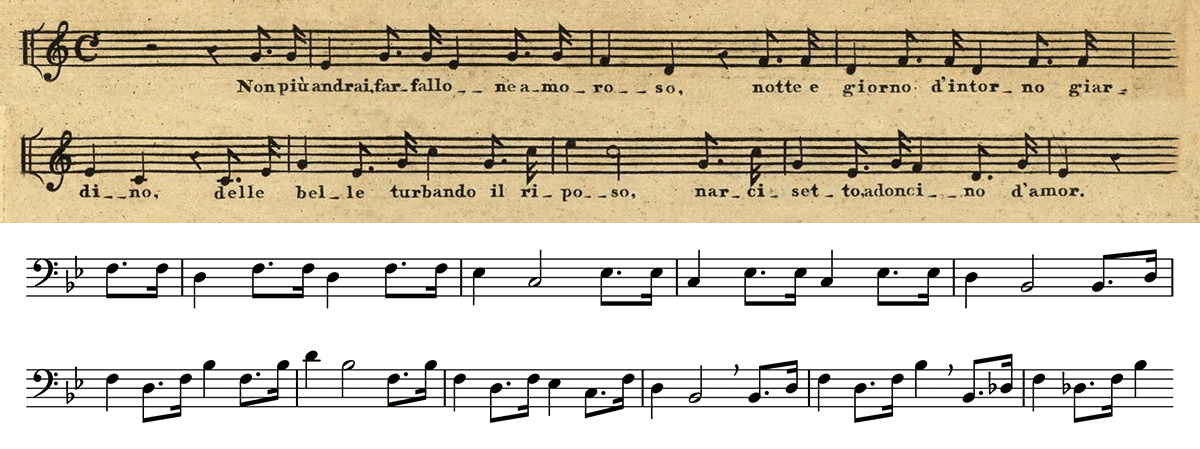

Top: the opening of Figaro's aria "Non più andrai," from Simrock's 1796 piano/vocal score. Bottom: MM. 8-17 of my mvt. 1 cadenza

The second half of this passage is almost the inversion of my modified version of the opening motive of the concerto, and complements it well. Also, it seemed fitting to quote this here because the concerto already has a connection to the opera: Mozart later reused the opening motive of the second movement in the aria “Porgi amor.” “Non più andrai” (sung by Figaro) is the last aria in Act I of Le Nozzi di Figaro, while “Porgi amor” (sung by the Countess) is the first aria in Act II. So, this is my own little nod to Mozart’s self-borrowing.

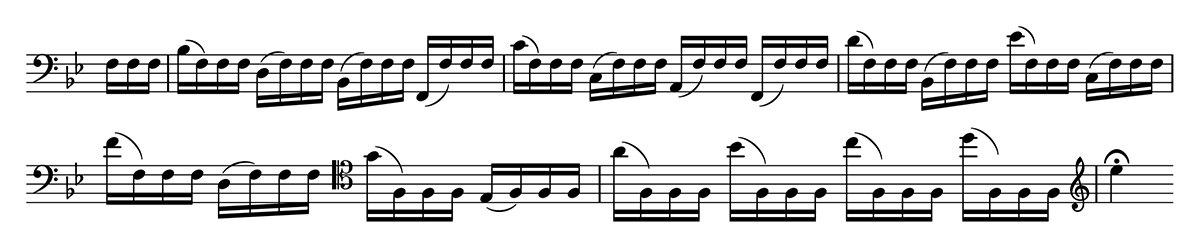

A second quotation in the mvt. 1 cadenza allowed me to hit all three goals: it is based on a passage from the Turkovic cadenza I’d used previously (goal #2), it draws on material from the concerto itself (goal #1), and it allows me to show off two of my strengths: fast tonguing and high register facility (goal #3). I always felt a little restricted in Turkovic’s version of this passage—it’s meant to accelerate, but it’s also too short to build up the kind of speed I wanted. For my version I extended it by seven beats, which also allowed me to push much higher in the bassoon’s range.

MM. 24-28 of my mvt. 1 cadenza. The beginning of this passage is taken from one of Milan Turkovic's cadenzas; I extended it by seven beats to end on E-flat instead of F.

There’s actually yet another level of quotation going on here; Turkovic took this passage from a cadenza written by Romanian-Viennese musicologist and composer Eusebius Mandyczewski (1857–1929). So, I’m quoting Turkovic quoting Mandyczewski paraphrasing Mozart.

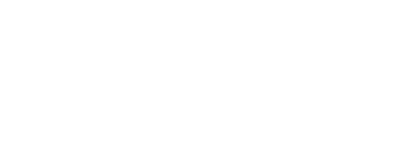

The first idea I jotted down was an ending for my mvt. 1 cadenza (shown below), and I don’t think it ever changed. This passage is solidly in the pursuit of showing off my high range (goal #3), and as such doesn’t strictly fit within period-appropriate performance practice.2A 1780 fingering chart by bassoonist Pierre Cugnier goes up to high F, but there's little evidence for anyone playing stratospheric notes in performance before Carl Almenräder in the early nineteenth century But even if it goes higher than bassoonists in Mozart’s time were likely to have played, I feel that it’s in the spirit of cadenzas as vehicles for showing off.

This passage works chromatically up to an extended high F (top of the treble clef staff). And just when you think that’s high enough, it continues up chromatically to G. In performance I added to the deception by putting a long decrescendo on the F, as if fading away, before coming back up to forte to continue up to G. In the written-out version of my cadenzas (downloadable below), I’ve provided an alternate ending for those who’d rather avoid the high G.

Watch the first movement cadenza:

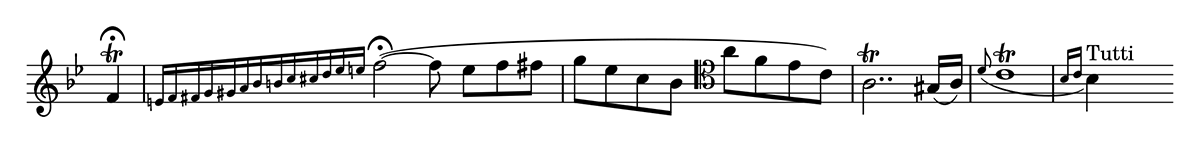

My process for writing the second movement cadenza was much the same. But in keeping with the movement’s character, I focused on beauty much more than virtuosity. Also, not wanting to go overboard with quotation, I used only one motive from the concerto itself and didn’t quote any other works.

The end of this passage comes from the movement’s recapitulation, although I’ve taken it down an octave here. I use the same motive, modified only so that it descends every time, to get there from what had come before.

As far as I know, the rest of my Mvt. 2 cadenza is original material (although it’s certainly possible that parts of it were unconsciously inspired by some of the many cadenzas I read through at the beginning of my process). Here’s the second movement cadenza:

Download the Cadenzas

If you’d like to try my cadenzas out for yourself, you can download a PDF below. If you use them in performance, please let me know!

![]() Wells-Mozart-Cadenzas.pdf (Released under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 3.0 license)

Wells-Mozart-Cadenzas.pdf (Released under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 3.0 license)

Notes:

- 1Sarah Anne Wildey, “Historical Performance Practice in Cadenzas for Mozart’s Concerto for Bassoon, K. 191 (186e)” (DMA Diss., University of Iowa, 2012).

- 2A 1780 fingering chart by bassoonist Pierre Cugnier goes up to high F, but there’s little evidence for anyone playing stratospheric notes in performance before Carl Almenräder in the early nineteenth century

- 1Sarah Anne Wildey, “Historical Performance Practice in Cadenzas for Mozart’s Concerto for Bassoon, K. 191 (186e)” (DMA Diss., University of Iowa, 2012).

- 2A 1780 fingering chart by bassoonist Pierre Cugnier goes up to high F, but there’s little evidence for anyone playing stratospheric notes in performance before Carl Almenräder in the early nineteenth century

6 Responses

Your article is MOST interesting. You certainly left no stone unturned. I had enjoyed hearing the cadenzas many times before reading this and understand and like them even better now. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks, Carol!

[…] Wells discusses composing cadenzas for the Mozart bassoon concerto (and shares his finished […]

Hey, on your third footnote:

You’re right, it’s a bit crazy that they go up to high F (if I’m correct it’s on a 5 key instrument — no vent keys). However, Antoine Dard’s Op.2 (1752) bassoon sonatas have a high D coming out of nowhere in them (he was one of the paris opera bassoonists).

With my Heirich Grenser (8 keys) instrument (he was making bassoons in the 1770s into the 1820s) I can get up to high D and on a good day high Eb. Likely the instrument would have been more popular in Dresden during Mozart’s early life than anywhere else, however by the later years they were going all over the place.

So, yes, high G not exactly historically appropriate, but not as far off as you might think.

Thanks for taking the time to document your process and I really enjoyed your performances. Two thoughts (I’m being over-critical here to further discussion):

1. In terms of extremes in register I’d personally think less about what is stylistically correct for the era and more in terms of implications to the greater work — for example does hitting extreme register notes diminish the emotive effect of notes scored by the composer later (or earlier on re-listening) in the piece.

2. There is some extended sequencing of motif that I felt goes on a little long (starts to feel like a technical exercise). I feel that this could be avoided by either smooth development/transformation of motif or a free/vocal ending to the phrase, or a progressively more strongly felt rhythmic pulse through that section.

Disclaimer:

My improvisation/writing is learned from a wider range of genres than just European concert music and my orchestration knowledge is learned mainly from orchestral music written 100+ years after this piece, so my perception won’t be uniquely limited to my taste in Mozart’s style.

Thanks for your thoughts! (And sorry to be so slow in replying).

1. The highest note Mozart wrote in the solo part is a B‑flat above middle C. It occurs twice in the first movement, so the Mvt. 1 cadenza follows them. The nearby As and Gs do occur in later movements, but I don’t think any of those instances hinge on an extreme of range for emotive effect.

2. Fair enough! This was my first crack at writing cadenzas, and I’m not much of a composer. I’m sure there are more elegant ways to transition between some of my motives, and probably also just some judicious editing to be done of the motives themselves. But you also give some interesting interpretive ideas for how to improve the realization of what I’ve already got—thanks!